Author: Justice Offei Jr. Policy Analyst & Petroleum Engineer

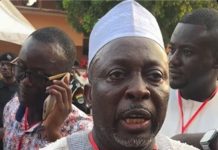

Speaking during his vetting before Parliament’s Appointments Committee on January 13, 2025, Energy Minister-Designate John Abdulai Jinapor revealed that the energy sector’s debt had escalated to over $3 billion as of January 12, 2025.

He has raised concerns about the growing debt burden in Ghana’s energy sector, describing it as a critical issue requiring urgent attention.

He noted that this increase compounded existing challenges, particularly the government’s financial obligations to Independent Power Producers (IPPs), which stood at $1.2 billion as of October 2024.

Mr Jinapor called for pragmatic solutions to resolve the debt crisis, ensuring the sustainability of the energy sector while safeguarding Ghana’s economic stability.

Looking at Ghana’s energy sector being swallowed by this vicious cycle of debt, we must begin to question the quality of leadership we have had at the Energy Ministry under both political parties.

The incompetence of our energy leaders will have only one major outcome: burdening the ordinary citizen. It is high time we conducted a deep diagnosis of the monopolistic nature of our energy market, which is dominated by state-owned entities with no private participation in the transmission, distribution, and retail segments of the energy supply chain.

Privatization in this context refer to competition and private sector participation without necessarily implying full ownership transfer.

The idea that high privatization is the only or primary solution for a competitive and efficient energy sector is not universally true.

While privatization and market liberalization have worked well in some countries (e.g., the UK, Chile, Philippines, USA), the success of these models depends on context-specific factors such as regulatory frameworks, institutional capacity, and market maturity.

You can equally find success in state-owned dominated energy sector (Norway, France) as well as hybrid success in countries like Morocco and New Zealand.

Consequently, while privatization can make the energy sector more competitive and efficient, it is not the only solution. For Ghana’s energy sector to achieve success, it must intentionally create a competitive and efficient market.

This can be achieved in a well-tailored model, ensuring competition in terms of pricing and quality delivery. Introducing competition in Ghana’s transmission and distribution part of the chain is a practical and necessary reform to address inefficiencies, attract investment, and improve service quality.

By allowing multiple private players to participate, Ghana can create a competitive energy market that drives innovation, reduces losses, and ensures reliable and affordable power for all citizens.

However, this reform must be implemented carefully, with strong regulatory frameworks and social safeguards to protect consumers and ensure equitable access. By learning from global best practices and tailoring reforms to Ghana’s unique context, the country can unlock its energy potential and build a sustainable future.

Understanding Ghana Energy Supply Chain

Ghana’s energy supply chain involves generation (hydro, thermal, renewables), transmission (GRIDCo), distribution (ECG/NEDCo), and consumption (residential, commercial, industrial). Power generation is the first step in the energy supply chain.

Ghana’s electricity is generated from a mix of hydro, thermal, and renewable energy sources. Key players include the state owned VRA, Volta River Authority (operates the Akosombo and Kpong hydroelectric dams, aslo manage thermal plant and solar farms) and Independent Power Producers (IPPs) like thermal plant operators Sunon Asogli, Cenpower, and Ameri Power.

Once electricity is generated, it is transmitted across the country through high-voltage power lines. GRIDCo (Ghana Grid Company) is responsible for transmitting electricity from power plants to distribution centers. It operates the National Interconnected Transmission System (NITS), which includes over 5,000 km of transmission lines. During transmission power is stepped up to high voltage for efficiant transmission over long distances. GRIDCO ensures grid stability and balances supply and demand in real time.

GRIDCo transmits electricity from power generation plants to bulk supply points (BSPs), which serve as distribution centers. These BSPs are strategically located across the country and act as intermediaries between GRIDCo’s high-voltage transmission network and the distribution companies (ECG and NEDCo). BSPs are substations where GRIDCo steps down high-voltage electricity to medium voltage for distribution.

ECG and NEDCo then take over to distribute power to homes, businesses, and industries. After transmission, once power reaches the BSP where electricity is stepped down ECG and NEDCo take over and get it distributed to homes, businesses, and industries.

Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) and Northern Electricity Distribution Company (NEDCo) are the key players in the distribution of power in Ghana. These distribution companies are responsible for maintaining distribution infrastructure (e.g., poles, transformers) as well as billing and revenue collection from consumers.

The most important infrastructure of the energy supply chain is revenue collection and distribution mechanism. This is a critical part of the supply chain, as it ensures funds flow back to generators, transmitters, and distributors. ECG and NEDCo collect payments from consumers and these revenues are then allocated through the Cash Waterfall Mechanism (CWM).

The Bold Solutions the Sector Needs

Now that you understand the nature of Ghana’s energy supply chain, you can journey with me through the purpose of this article.

Looking at the nature of debt level and the inefficiencies in the energy sector, it is indispensable to take a second look at the monopolistic nature of the Ghana energy sector where government control almost everything.

The Energy Legacy Debt & A Real-Time CWM Ghana can resolve its legacy debt and transition to a real-time CWM with a liberalized market by securitizing debt and renegotiating IPP contracts and automating payments via technology and smart meters.

Ghana’s energy legacy debt has become an albatross on the sector and that the Energy Sector Levy Act (ESLA) which meant to salvage the situation has become a vehicle for more debts.

ESLA was introduced in 2015/2016 with the aim to raise funds to pay off legacy debts through levies on petroleum products, electricity consumption, and public lighting.

This was to consequently restore investor confidence by demonstrating Ghana’s commitment to resolving energy sector arrears.

There was some initial success. Unfortunately, the misuse of ESLA proceeds , the over-reliance on ELSA as it became a permanent crutch rather than a temporary fix lead it to its failure.

In 2017, ESLA was converted into a special-purpose vehicle (ESLA PLC) to securitize debts and issue bonds. While this restructured debts, it did not eliminate them. By 2023, ESLA-related debts had ballooned to GH¢54 billion (about $5 billion), with the levy struggling to keep pace.

It is important to note that the nature of most existing IPP Contracts are major contributors to the level of debt and inefficiencies. In the context of Ghana’s situation, best practice will inform our decision along these considerations; Renegotiate to replace “take-or-pay” contracts with “take-and-pay” or capacity charge adjustments to align payments with actual electricity consumed.

For example, the Philippines renegotiated costly “take-or-pay” contracts with Independent Power Producers (IPPs) under the Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA). India and Mexico are other examples Deploy a debt-for-equity swaps approach: Offer these IPPs equity stakes in future renewable energy projects or privatized ECG/NEDCo franchises.

In South Africa, Eskom (state utility) also explored swapping debt for equity in new projects to reduce its $27 billion debt burden. Kenya and Morocco are other good examples to look at.

The structure of Ghana’s energy supply chain, particularly the Cash Waterfall Mechanism (CWM), operates on a credit-based system along the supply chain despite consumers paying upfront (via prepaid meters).

This seemingly contradictory setup stems from structural inefficiencies, historical practices, and market design flaws. Is it practicaly possible to implement a real-time CWM as best practice in Ghana? A real-time CWM ensures transparent, automated, and immediate payments across the supply chain.

We can achieve this by Digitize payments: using technology to track revenue from prepaid meters to generators in real time. Example: UAE’s blockchain platform for utility payments.Automate prioritization: Program the CWM to allocate funds instantly to stakeholders (fuel suppliers → generators → GRIDCo → ECG/NEDCo → legacy debt). Countries like UK and South Africa are good examples.

Prepaid Meter Integration: Link smart prepaid meters to the CWM to ensure consumer payments flow directly into the system, bypassing manual pooling by ECG/NEDCo.

Introducing competition in the transmission and distribution parts of the energy supply chain is a practical and necessary reform to address inefficiencies, attract investment, and improve service quality.

By allowing multiple private players to participate, Ghana can create a competitive energy market that drives innovation, reduces losses, and ensures reliable and affordable power for all citizens.

I offer some proposals from best practices, considering our local context in creating liberal market; Liberalizing Power Transmission Chain GRIDCo’s transmission network is critical to Ghana’s energy supply chain, but it requires significant upgrades to handle growing demand and integrate renewable energy.

The transmission chain is currently dominated by the state in the capacity of GRIDCo with no private firm participating.

There must be a political will to develop policies to empower eligible private firms to participate in this part of the supply chain.

This can be achieved in the following ways:Open Access Model: Allow private companies to use GRIDCo’s transmission infrastructure to transmit power, paying a regulated fee.

This model is used in countries like India and South Africa.Independent Transmission Operators: License private companies to build and operate new transmission lines m competing with GRIDCo Regional Franchise: restructure the transmission network into regional franchise, with private operators managing specific zones.

Liberalizing the Power Distribution Chain

This part of the supply chain is solely dominated by the state nonetheless ECG and NEDCo’s distribution networks are plagued by inefficiencies and revenue shortfalls.

Creating a competitive distribution and retail market should include; Retail Competition: Allow private operators to participate in the retail market where Consumers can switch suppliers to get better tariffs or services.

In UK, over 60 suppliers are participating. Smart Meters: Introduce Smart Meters to improve energy efficiency and billing accuracy Tariff: Allow suppliers to set tariff while ensuring fairness by Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) Distribution Franchise Models: Auction distribution franchises to private operators, as done in the Philippines.

Operators would be responsible for maintaining infrastructure, reducing losses, and collecting revenue.Performance-Based Contracts: Tie payments to operators to their performance in reducing losses and improving service quality.

Regional Competition: Divide the distribution network into regions, allowing multiple operators to compete within the same area. Regulatory Reforms a competitive market requires strong regulatory frameworks to protect consumers and ensure fair competition.

These among many others should be considered:Independent Regulator: Strengthen the Energy Commission and PURC to oversee the sector without political interference.

Cost-Reflective Tariffs: Ensure tariffs reflect the true cost of service, with targeted subsidies for low-income households.Transparency Mechanisms: Use robust technologies to track revenue flows and prevent corruption.Social Safeguards Creating a liberal market must not come at the expense of social equity.

Key safeguards include:Lifeline Tariffs: Maintain subsidized tariffs for low-income households.Universal Access: Ensure private operators serve rural and underserved areas.

Stakeholder Engagement: Involve consumers, workers, and other stakeholders in the reform process. The consequent outcome of creating a liberal and a competitive market through private participation includes improving efficiency and reducing losses, attracting investment, enhancing service quality and reducing government interference.

This approach focuses on creating a competitive energy market where multiple private players can participate in transmission and distribution, while the state retains ownership of critical infrastructure.