There are as many as 1.6 million viruses we know nothing about lurking in mammals and birds, and as many as half might have the potential to jump to humans and infect us. That’s an estimate, based on mathematical models, but the threat is clear. Six out 10 infectious diseases that strike us come from animals.

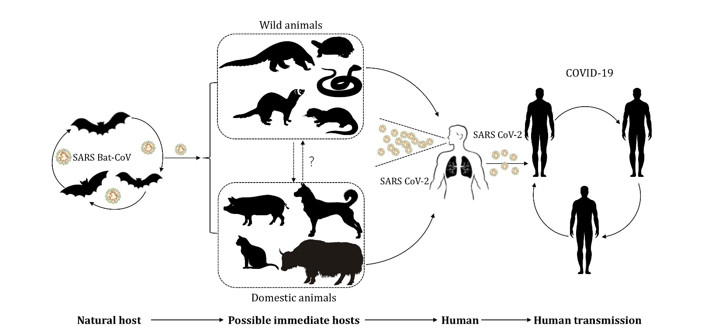

The list includes HIV/AIDS, Ebola, MERS, SARS, and in all probability COVID-19. Viruses have been moving between organisms for millions of years . And not always in a way that causes harm: Animals and humans alike host millions of different microorganisms, many of which are beneficial.

“We live in an essentially microbial world, and we are actually complex ecosystems comprising a whole lot of microorganisms,” says Fabian Leendertz, head of the Epidemiology of Highly Pathogenic Microorganisms group at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin. “Some are pathogenic, but most of them live at peace with us.”

As human interaction with wild animals grows, so does the risk that disease organisms will leap from them to us.

For those that do harm humans, the first step is to come in contact with us. And that’s becoming more and more likely as we invade pristine forests in search of food, building materials, space for commercial developments or land upon which we can create new grassland for our livestock — or catch critters for bushmeat, pets or the “wildlife selfie” trade .

Population growth, economic development and habitat destruction were pushing humans up against wild animals with deadly viruses, while growing cities and global air travel meant any germ that jumped to us could readily travel long distances. But more than that, scientists actually predicted precisely the kind of virus we are now fighting — a respiratory coronavirus from bats. In 2005, Zhengli Shi, now director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, found coronaviruses in bats that closely resembled the SARS virus that started in China and almost went pandemic in 2003. In 2015, both Shi’s lab and another in North Carolina discovered some of these bat viruses could infect human airways and cause severe disease without having to undergo any changes. The research team put “potential for human emergence” in the title of their scientific article so no one could miss it-Emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV underscores the threat of cross-species transmission events leading to outbreaks in humans.

Yet we ignored the warning. There was no emergency program aimed at developing a coronavirus vaccine or antiviral drugs, no global alert to watch for new coronaviruses in humans, no blanket ban on bat-derived products — not even pandemic response plans for anything but pandemic flu.

Scientists agree that more viruses capable of causing a global pandemic will emerge , says Amesh Adalja of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, who predicted respiratory RNA viruses were a particular threat a year before the emergence of Covid-19 — a respiratory RNA virus.

Virologists are also worried about several flu viruses, and about the lethal Nipah virus of Asian fruit bats, which is evolving the ability to spread person-to-person. If nothing else, there are lots more coronaviruses — and probably infections we have no clue about yet. The million-dollar question is, what can we do now to prepare so that we can prevent any of them from causing another pandemic?

The good news is that Covid-19 has taught us the risk is real, and hideously expensive, making us more likely to finally act on the warnings. The question is whether we actually will.

First, say experts in emerging diseases, we need surveillance of viruses circulating in humans, and perhaps in animals as well, to spot any new infection fast. The 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), a treaty governing the management of outbreaks that could cross borders, requires rich countries to help improve surveillance in poor ones — but they largely have not, says David Heymann of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who helped lead the negotiations that led to the current version of the IHR in 2005.

“Rich countries have funded international efforts” such as the new emergency response capability at the World Health Organization (WHO), installed after the agency responded slowly to an Ebola outbreak in 2014, Heymann says. “But it would be better to help poor countries take charge of managing their own health situation themselves.”

China’s hospitals have a system that automatically alerts central health authorities of any unusual clusters of disease, a good way to spot when a new virus starts spreading in people. However, Wuhan officials trying to keep the Covid-19 outbreak quiet silenced it last January, allowing the novel coronavirus to spread for weeks before serious containment measures were taken, ultimately letting it get around the world. A more fail-safe version in more countries would help to better contain potential pandemic-causing disease organisms.

Second, we must diagnose infections. Most illness is diagnosed symptomatically, for example as a cough or fever or rash; the germs responsible for the symptoms are rarely identified, even in modern hospitals. China’s pneumonias started in November, but doctors reportedly didn’t do a diagnostic test to identify the germ responsible until late December. And that revealed a new coronavirus only because China has state-of-the-art DNA and RNA sequencing technology available to hospitals. Not all countries could have spotted it.

New technologies can in theory identify germs we haven’t even seen before. The novel IRIDICA platform , based on a mass spectrometer, spotted the 2009 pandemic flu when it first hit the U.S. But the machine was taken off the market in 2017 by the medical technology company Abbott because of low demand. Not enough big hospitals saw the need for such capability to buy it, says Ranga Sampath, chief scientific officer of FIND , a nonprofit dedicated to developing diagnostics in Geneva, Switzerland, who was involved in developing IRIDICA.

Other diagnostic technologies, like the rapid tests now being used to screen people for Covid-19 infection, could also be used to screen for novel infections more systematically. But there is no way to sell technologies aimed at viruses that may never go pandemic, and that hampers progress, says Sampath.

A third line of defence would be to proactively develop vaccines and therapeutics. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) was set up in 2017 to fund the development of vaccines for potentially pandemic viruses. But progress has been slow; the only coronavirus vaccine being funded before Covid-19 was for MERS, an existing disease with a potential market. Efforts to set up a similar coalition for antiviral drugs have never gotten off the ground. Covid-19 could inspire more urgent efforts.

A logical focus might be on the new infections already attacking humans, which would be discovered through improved surveillance. But some virologists argue we should learn about viruses before they find us, not after. The Global Virama Project (GVP), a non-profit organization, is trying to raise US$3.7 billion over the next 10 years to genetically sequence and geographically map the half-million viruses in animals that belong to virus families that can infect humans.

But Adalja and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Centre for Health Security argue that such a survey won’t tell us which of the thousands of new viruses discovered are dangerous or likely to emerge. Only tracking disease in humans will do that.

The answer might be a bit of both. Starting in 2013, Peter Daszak, head of the U.S.-based research non-profit Eco Health Alliance , and among the scientists backing the GVP, worked with Shi to discover SARS-like coronaviruses in bats, as the GVP advocates. But the team also found which of those viruses could infect people — plus evidence that, near bat caves in China, they already were. One of those viruses eventually caused Covid-19.

The problem is that neither discovery led to an urgent program of anti-coronavirus research and development.

David Morens, senior scientific advisor to Anthony Fauci at the U.S. National Institutes for Allergy and Infectious Disease, suspects we need dedicated institutions whose job it is to survey worrying viral discoveries, decide which require a response, and see it gets done. No one is now charged with connecting all those dots.

“We all have a stake in preventing pandemics, and the problems can’t be solved by any one country. So we should solve them together, as we have nuclear weapons.” — David Morens“We all have a stake in preventing pandemics, and the problems can’t be solved by any one country,” he says. “So we should solve them together, as we have nuclear weapons,” where a U.N. agency monitors nuclear industries. But, he says, the WHO doesn’t have the resources to monitor global disease. “No one’s in charge.”

For example, Wuhan doctors knew last December that the virus spread person-to-person, but Chinese officials claimed to the WHO that it didn’t, possibly to avoid panicking people. Earlier transparency might have led to earlier controls and a smaller epidemic.

But the WHO had no right to go into China and verify whether China’s reports were true. Treaties for chemical and nuclear weapons permit international inspectors to verify countries’ declarations about those things. Diseases pose arguably a worse risk, but under the IHR, they are the sole concern of the country they happen to strike first. If the WHO could inspect and verify countries’ declarations about disease — and help countries build their surveillance capability while they’re at it — we might be less at the mercy of countries’ inclination or ability to report disease.

Ultimately, to prevent pandemics we need to prevent wildlife viruses from leaping from nonhuman animals to people.

Much attention has focused on the wildlife trade, as some early cases of Covid-19 had links to a wet market in Wuhan. Certainly, markets pose a risk, says Daszak. But genetic and epidemiological evidence that Covid-19 started on that market is weak. Other dangerous activities have gotten less investigation — for example, the widespread use in China of dried faeces from the very bats that carry Covid-like viruses as a traditional eye medicine.

One way to reduce the threat of pandemics is to factor the cost into land use decisions, since activities such as deforestation can enhance the chance that disease organisms will move from wildlife to humans. Photo courtesy of Axel Fassio/CIFOR from Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

One way to keep humans and bats apart may be to factor the potential costs of pandemics into how we manage land use. The destruction of wildlife habitat, which brings people and wild species into new kinds of contact that can spread viruses, makes stressed, hungry wildlife more likely to spread infection.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) brings together scientists and policy experts to advance conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. In October IPBES estimated that spending US$40 billion to US$58 billion per year on disease surveillance, and reducing wildlife trade and risky land use changes, would significantly reduce pandemic risk — a bargain compared with the estimated US$8 trillion to US$16 trillion cost of just this pandemic — and that was only until July. Timber companies and the like might be eager to cooperate, says Daszak, a lead scientist on the IPBES report, if they were liable for damages from infections unleashed by their activities.

Meanwhile, the Covid-19 crisis will end. A vaccine might be ready soon. It won’t immediately stop all Covid-19 circulating. However, it could be coupled with rapid, frequent, inexpensive tests to see who is carrying the virus, coupled with strict quarantine of infected people and their contacts, to safely re-open businesses, schools and restaurants, says Michael Mina of Harvard University, a leading expert on immune reactions to viruses. The air travel industry is already introducing rapid tests for the virus at some airports in a bid to replace the quarantines some countries now require of new arrivals, which have vastly reduced travel.

Covid-19 has revealed the true cost of our destruction of biodiversity. But while normal life might one day return, the complacency that led to this pandemic must not, or, disease experts agree, we will certainly have more, and potentially worse pandemics. Covid-19 has revealed the true cost of our destruction of biodiversity. As we have seen, to control outbreaks, countries must start watching more closely for novel infections, sharing that information, and making far better pandemic plans. But they must also start trying to stop novel outbreaks from happening at all, by vastly reducing the destruction of nature that allows animal viruses to jump to us in the first place.

Not only that, but people who do not see our natural planet as worth conserving in its own right may now see another point. Destroying nature leads to deadly, destabilizing, very expensive pandemics. If campaigns using cute pandas can’t end the destruction, maybe mounting death tolls — and economic devastation — will.

Compiled by Philip Kyeremanteng BSc MSc CEnv CSci

Ref

- Solutions Journalism Network

- COVID-19 by Debora MacKenzie | Hachette Book Group

- We are creating conditions for diseases like COVID-19 to emerge | Ensia

- Global Virome Project

- A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China (nih.gov)

- Can we predict — and prevent — the next big pandemic? | Ensia

- A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence | Nature Medicine

- Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States – PubMed (nih.gov)